Ruohua Han Dissertation Defense

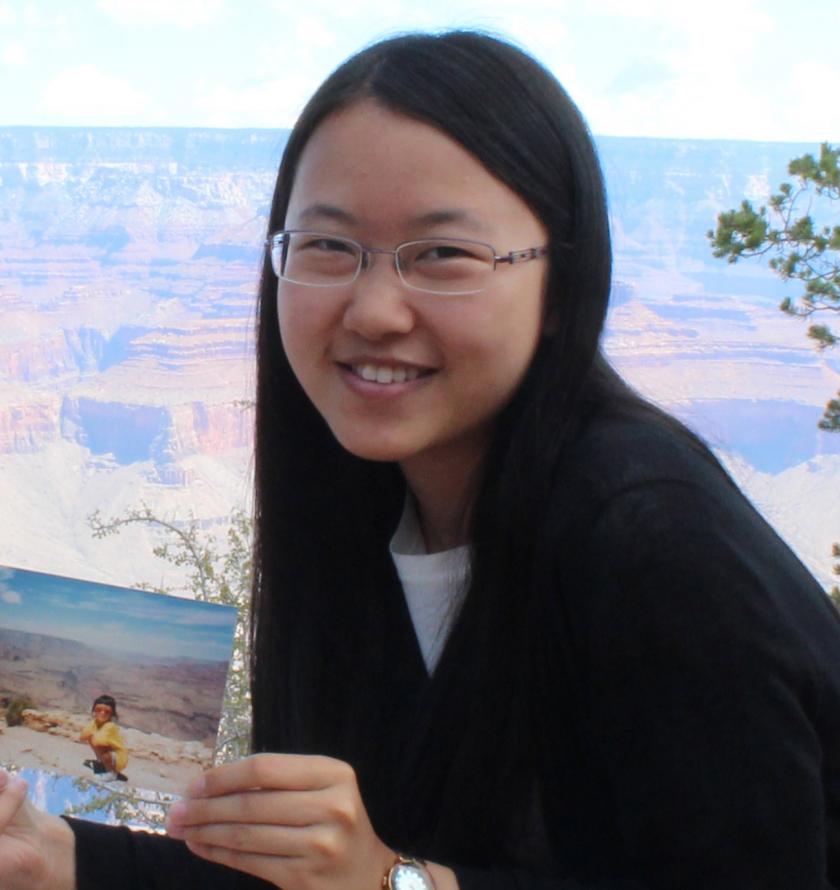

Doctoral candidate Ruohua Han will defend her dissertation, "Exploring the Sharing of Autobiographical Memories and Memory Objects in Chinese Families."

Abstract:

Autobiographical memories can be shared, withheld, and received in families as they can exist in various forms. This dissertation is an exploratory study that examines everyday activities of sharing, withholding, and receiving autobiographical memories in Chinese families and how memory objects can be involved in such activities. I used semi-structured interviews and supplementary ethnographic fieldwork to gather information from 32 Chinese participants living in urban areas of Xi’an (Shaanxi Province) and Beijing in China. My goal what to understand how people experienced activities of sharing and receiving autobiographical memories, their decision-making considerations about what to share and withhold, and what they thought about any memory objects that might be used.

During the data analysis, providing and receiving parental guidance in families emerged as a particularly significant life context where sharing memories and interacting with memory objects can take on rich meanings. The findings revealed that parental information practices of sharing memories with children could be characterized into four approaches: the open referential guiding approach, the reserved referential guiding approach, the preventive role modeling approach, and the motivational role modeling approach. As identifiable tendencies that collectively form a fluid continuum of practices, the four approaches reflect how key elements such as parental beliefs about how children learn, navigating trust and risk, framing memories for children, and shaping parent-child power dynamics can interact. Memory objects can play three roles when autobiographical memories are shared and received in families in contexts and situations that may impact parental guidance. They can affect the shaping and reshaping of the images of parents, help parents to provide guidance for children (especially adolescent children) that is sensitive to their characteristics, and help parents to retain memories of parenting or to retain/expand the parental guidance value of their memories. On a fundamental level, memory objects can play these roles because they can function as “natural traces” of the past, exist in different cultural/media forms with various characteristics, be used individually or in sets, and stay relatively durable across time and space.

The findings suggest that Chinese parents’ approaches to sharing memories with children may reflect broader societal trends in China, which are characterized by swift changes in generational life experiences and tensions between traditional and newer ways to conceptualize parent-child relationships and perform parenting. Under this background, memory objects help to weave together a web of activities such as information sharing, receiving, exchanging, encountering, and avoidance in families, offering opportunities for illuminating, leveraging, questioning, and negotiating past personal identities and their meanings for different generations of family members.

Her committee includes Associate Professor Lori S. Kendall (chair), Associate Professor Jodi A. Schneider, Assistant Professor Rachel M. Magee, and Associate Professor Linqing Ma (Renmin University of China).

For any questions, please contact Lori Kendall.