originally published in the Fall 2015 issue of Intersections magazine

The Chevy Suburban towing a U-Haul trailer pulled up to the decommissioned middle school in Metropolis, Illinois, population 6,000. A special kind of 4-H camp was about to begin.

The four leaders—Gabriel Ewing, Jessica Nelson, Colten Jackson, and Virginia McCreary—unloaded the equipment: almost thirty laptops with Intel i5 processors; a thirty-watt mini laser engraver; six 3-D printers; six digital embroidery sewing machines; six electronic vinyl cutters; six soldering stations; and enough small-board electronics for up to a dozen participants to make mini robots out of puff balls.

This camp is part of an exciting pilot project, Digital Innovation Leadership Program (DILP), undertaken by three groups with interlocking missions: GSLIS’s Center for Digital Inclusion (CDI), the Champaign-Urbana Community Fab Lab, and the University of Illinois Extension, the latter of which has provided GSLIS with $300,000 to run the project. CDI provided financial support for the four camp leaders to receive fab lab training at MIT.

CDI’s mission focuses on improving the democratic, social, and economic vitality of communities through the use of information technologies. Extension, which runs 4-H camps across the state, is looking for ways to bring its programming to under-served communities like Metropolis. And the Fab Lab is part of a nationwide maker movement that provides spaces with innovative, technical tools and encourages people to experiment and make things.

“As the world changes and becomes more reliant on technology, we need to develop and enhance opportunities to make our communities more digitally inclusive,” said Jon Gant, GSLIS research associate professor and CDI director who is the principal investigator on the grant. “It was great to partner with Extension and the Fab Lab and put our research into practice. Digital inclusion is not just about access; it’s also about the adoption and use of tools.”

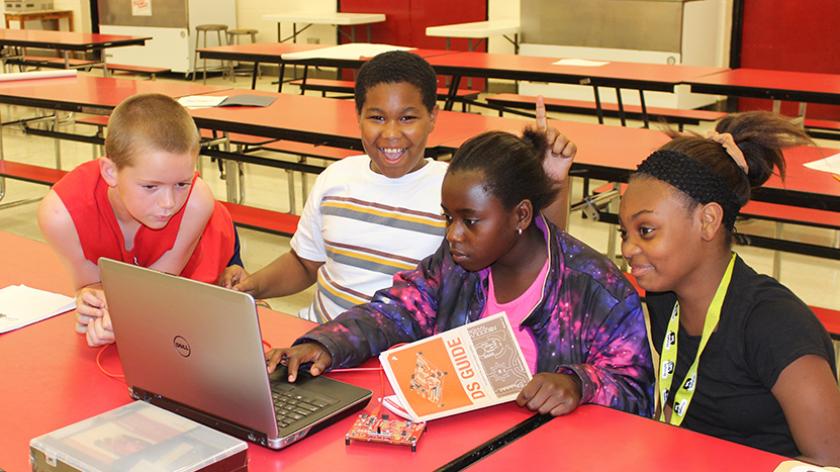

Once the equipment was set up, the day campers began to wander in. Ewing asked the assembled children, ranging in age from eight to twelve, “What have you made recently? Did you make breakfast this morning? Did you make your bed? Did you make a mess?” This kind of patter got the group giggling but also thinking. Ewing told the children what to expect from this day camp: they would use technology to create and invent whatever they could dream of. Every day of the camp, each participant made something he or she could take home, whether it was a notebook with a laser etching, a sticker, or an Arduino robot made of fabric and puff balls.

This type of rapid prototyping allowed the campers to make things quickly, which, in turn, allowed them to also test and improve their creations immediately. In addition to learning by doing, it also was about experimentation and failure, experiences that tie into critical thinking skills.

“The idea is to demystify technology,” said Ewing. “Everybody can be an innovator. An innovator is not necessarily a white dude in a lab coat.”

Last summer, multiple camps took place in southern Illinois, Peoria, and the Champaign/Danville area. At the end of every camp, the organizers made sure to hold an open-house style celebration to which they invited the campers, their families, and decision makers and opinion leaders within the community.

“The focus is not exclusively on the technology itself so much as opportunities for people to harness technologies in ways that allow them to amplify their interests in building a more resilient, just, and inclusive community—and how we help people exercise choice to achieve those goals,” said Martin Wolske, CDI senior research scientist, who specializes in bringing together technology and community.

Prior to the camp sessions, several teens came to the Illinois campus to get trained in the use of the Fab Lab tools. Thereafter, they participated in the camps with Ewing, Nelson, Jackson, and McCreary, providing support and knowledge, and even helping to instruct. The training allows them to continue to instruct and support their communities when the program is over.

Kirstin Phelps, GSLIS doctoral student and DILP project manager, was impressed with the energy of these teen teachers. “I was struck by their very good rapport with their peers and with the younger participants,” said Phelps. “They could connect with them in a way college students couldn’t.” Phelps also is interested in the leadership around how different stakeholders work together to organize projects like DILP in their communities.

Beyond bringing the camps to town, the researchers also identify specific needs for and obstacles to establishing permanent Fab Lab-type centers for these rural communities. They ask questions such as: “Do individuals interested in these kinds of projects know who to go to for knowledge, money, or physical space within their community?” “How can we create a forum for people interested in the maker movement and digital literacy?”

“The project is really about how to think about a challenge and how to solve it,” said Phelps. “It’s as much about social practices and mindsets as it is about technology. We want to get people to think about their own agency and how they can use technology to help.”